Episode: Vagus, Baby, Vagus

The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve—also known as CN X—and it is the longest and most complex of the cranial nerves. It is a central player in the parasympathetic nervous system and serves as the primary communication highway between the brain and the body.

In this episode, we are going to cover what the vagus nerve is, what it does, how it relates to stress, digestion, and emotion, and how you can stimulate it to regulate your nervous system.

Let us begin with the basics.

[Segment 1: Structure and Function]

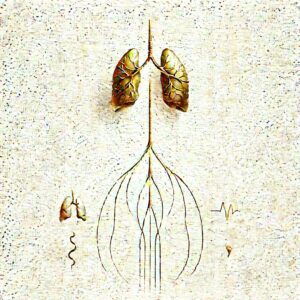

The vagus nerve originates in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem. From there, it extends through the neck, into the chest, and down into the abdomen—innervating major organs including the heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, and digestive tract.

“Vagus” comes from Latin for “wandering,” which is appropriate—it quite literally wanders through the body.

It is a mixed nerve, meaning it contains both motor and sensory fibers. Approximately 80% of the fibers in the vagus nerve are afferent—they carry information from the body to the brain. Only 20% are efferent—transmitting signals from the brain to the body.

In short, your brain is constantly listening to your body, and the vagus nerve is the main conduit for that sensory information.

[Segment 2: The Parasympathetic Nervous System]

The vagus nerve is the primary component of the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. Its job is to counterbalance the sympathetic nervous system—what we commonly call the “fight or flight” system.

Parasympathetic activity is associated with the “rest and digest” state.

When the vagus nerve is activated, it:

- Slows the heart rate

- Stimulates digestive activity

- Promotes relaxation

- Reduces inflammation via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway

- Modulates mood and emotional regulation through feedback loops with limbic structures

Think of the vagus nerve as the body’s internal peacekeeper. When active, it signals to the body and brain: “You are safe. You can rest.”

[Segment 3: Vagal Tone and Health Outcomes]

The strength and flexibility of vagal signaling is known as vagal tone. Higher vagal tone is associated with:

- Improved heart rate variability (HRV)

- Better emotional regulation

- Reduced risk of cardiovascular disease

- Lower levels of systemic inflammation

- Faster recovery from stress

- Improved social engagement and empathy

Low vagal tone, conversely, is associated with:

- Anxiety and depression

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Autoimmune dysfunction

- Emotional dysregulation

- Poor sleep quality

Vagal tone is not fixed. It can be improved with consistent training and behavioral practices.

[Segment 4: Stimulating the Vagus Nerve]

There are several evidence-based methods for stimulating vagus nerve activity. These are non-invasive and do not require equipment.

- Slow, Deep Breathing

Breathing at a rate of 5–6 breaths per minute, especially with prolonged exhalation, activates the vagus nerve. This enhances parasympathetic tone and reduces sympathetic arousal. - Cold Exposure

Brief exposure to cold, especially on the face or neck (cold water splash, cold packs), can stimulate the vagus nerve via the mammalian dive reflex. This slows the heart and calms the nervous system. - Singing, Humming, Gargling

The vagus nerve innervates the vocal cords and muscles at the back of the throat. Activities that vibrate this region stimulate vagal afferents. - Meditation and Mindfulness

Practices that promote present-moment awareness and interoceptive attention—such as body scans or breath awareness—modulate vagal activity through top-down cortical regulation. - Social Connection

Positive social interactions—especially those involving eye contact, prosody, and co-regulation—engage the social engagement system, which is vagus-mediated through the myelinated fibers originating in the nucleus ambiguus. - Vagal Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

There are also medical devices—approved for treatment-resistant depression and epilepsy—that provide electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve, typically via an implanted electrode in the neck. However, this is reserved for clinical populations.

[Segment 5: Vagus Nerve and the Gut-Brain Axis]

The vagus nerve plays a central role in the gut-brain axis—the bidirectional communication between the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system.

It carries information from the gut microbiome to the brain, influencing mood, cognition, and behavior.

For example, certain probiotics—classified as psychobiotics—have been shown to affect anxiety and depression symptoms through vagus-mediated pathways.

When vagal communication is impaired, gut dysfunction and mood disorders often co-occur.

[Conclusion]

The vagus nerve is not a fringe topic. It is a foundational structure in neurobiology, immunology, and psychophysiology.

It links your emotional life to your physical body. It tracks your internal state and tells your brain whether or not you are safe. It modulates your heart, your gut, your immune system, and your sense of connection to others.

It is a real-time bridge between biology and experience.

Learning to stimulate and support your vagus nerve is not just a self-care practice. It is a nervous system intervention.

So the next time you feel overwhelmed, anxious, or dysregulated—remember this:

Vagus, baby. Vagus.

And breathe.

Would you like the next episode written in this same fashion? I suggest we tackle “Cortisol & Me: A Toxic Romance” or perhaps “The Prefrontal Cortex Needs a Nap”. Let me know your preferred direction.

You said:

“Cortisol & Me: A Toxic Romance”

ChatGPT said:

Excellent choice. Here is the full, detailed script for the next episode of The Nervous System Diaries, titled: